This is an extended version of a series of tweets from 16 June on the Grenfell Tower disaster. I felt compelled to put it together because it’s not often I get affected by something in the news, for reasons I explain at the outset.

It took, I feel, a disaster of this magnitude, something this horrific, in the richest borough in the country, for so many to finally understand just what a different life the poor lead. And that’s my take on it. This is about the chasm that exists between the classes and my experience of being on the wrong side of that chasm in London and the way in which poverty and bad housing impacts on your life.

Do me a favour. If you retweet this, please don’t call it a ‘Long Read’.

Since the crash of ’08, hundreds of thousands of Londoners have existed on bread and water, cut adrift, struggling through the days, working harder than ever to make ends meet only to see little or no change in their personal circumstances. It took me some time to realise not everyone in London had been affected by the crash. Cab driver friends would tell me how they were still taking the same old people out to their usual restaurants and glitzy bashes and I slowly became aware of a widening class divide in the capital. My own experience, the way my life came apart during the crash, changed me as both a writer and a person. I had long blocked out my horrific housing experiences that stretched back to growing up in the seventies and kept turning out work that was bought on a regular basis by TV broadcasters, work that rarely touched on the unusual circumstances in which I had grown up. There was the occasional housing-related piece for Radio 4 in the mid-noughties, but I only ever revisited that life in my work occasionally.

In 2010, finally, two years after a pilot, with my TV career going tits up, I launched a podcast with my childhood friend Micky Boyd. The first episode was in fact my last week in my latest privately rented flat fifteen minutes north of Clapham North where I grew up. The next 30 odd episodes came from a bed and breakfast I had to move into for six months (I finally got out on Christmas Eve 2010), and then I recorded from two different homes where I lived with friends until I was back on my feet. For the last 7 years in my radio, writing and podcast work, I have documented the struggles, in an often light hearted and original way I feel, of being on the wrong side of the class divide. The final (live) radio series of Daniel Ruiz Tizon is Available on Resonance FM in October – December 2015, had community and change as its themes as I looked at the impact of gentrification on my neighbourhood. You can find that series on this site, here: goo.gl/5neDqD

It took several years to understand what had happened to my life but I also used that time to speak to many other people who had also seen the quality of their lives decline markedly since the financial crash, though I’m not sure how many of them had given serious thought to buying a 36-piece Smart Price cutlery set from Asda in the lost summer of 2011. So many people had their own stories and I always made time to hear them, hoping it might help me understand my own story better. Everyone I spoke to had made mistakes along the way and many like me had found it hard to forgive themselves the errors that had set them back years in their efforts to recover the heights of their old lives.

In recent years, I have tended to be something of an automaton when it comes to tragedies. The post '08 austerity and belt tightening did that. You can become absorbed in your own daily struggles and the dread of watching the cost of the All-Butter 29p LIDL croissant rise and rise. But in the Grenfell community I have seen coming together on the news in the aftermath of something that I hope will change things for the better in this country, has been a blast from the past for me. In those people I see the various communities and faces I grew up with in southwest London back in the day.

My old neighbourhood of Clapham, where I spent my first two decades, has long not been for me. Brixton in southwest London, more of which later, has also changed. In the early noughties, the balance was right. The market was still vibrant, the old community was still there, the influx of middle class newcomers unable to afford Clapham was yet to overwhelm the area. It was that rare case of a southwest London postcode having the balance right between the classes and it worked for the most part. Now of course, northbound, heading towards the river, it’s the same story in Vauxhall. So much of Vauxhall’s history has been lost in the last two or three years as old buildings make way for hideous glass-heavy luxury builds that exist cheek by jowl with the numerous council estates that seem to occasionally check the advance of the cranes.

Grenfell is a horror the like of which was far more common decades ago. It’s only been two days but it seems longer to me already. That’s the thing about disasters. I was at school when the King's Cross fire happened but very quickly it seemed like the horror of King's Cross had been there my entire life. Zeebrugge. Hillsborough. Paddington. The Clapham Junction rail disaster. They all feel like that and I’m sure Grenfell will join that cast of horrors.

Grenfell has really rattled me. Fires were not an uncommon sight in my childhood. I remember a big fire in Brixton in the early 80s, opposite Mothercare. Less than ten minutes from Brixton, still in SW9, two West Indian girls my sibling and I used to play with as kids died in a house fire on our road one Saturday night. Moreover, it wasn’t unusual to see burns victims your own age, horrifically disfigured kids. I often wonder what happened to them because it’s rare these days to see similarly disfigured adults so where did these young burns victims disappear to?

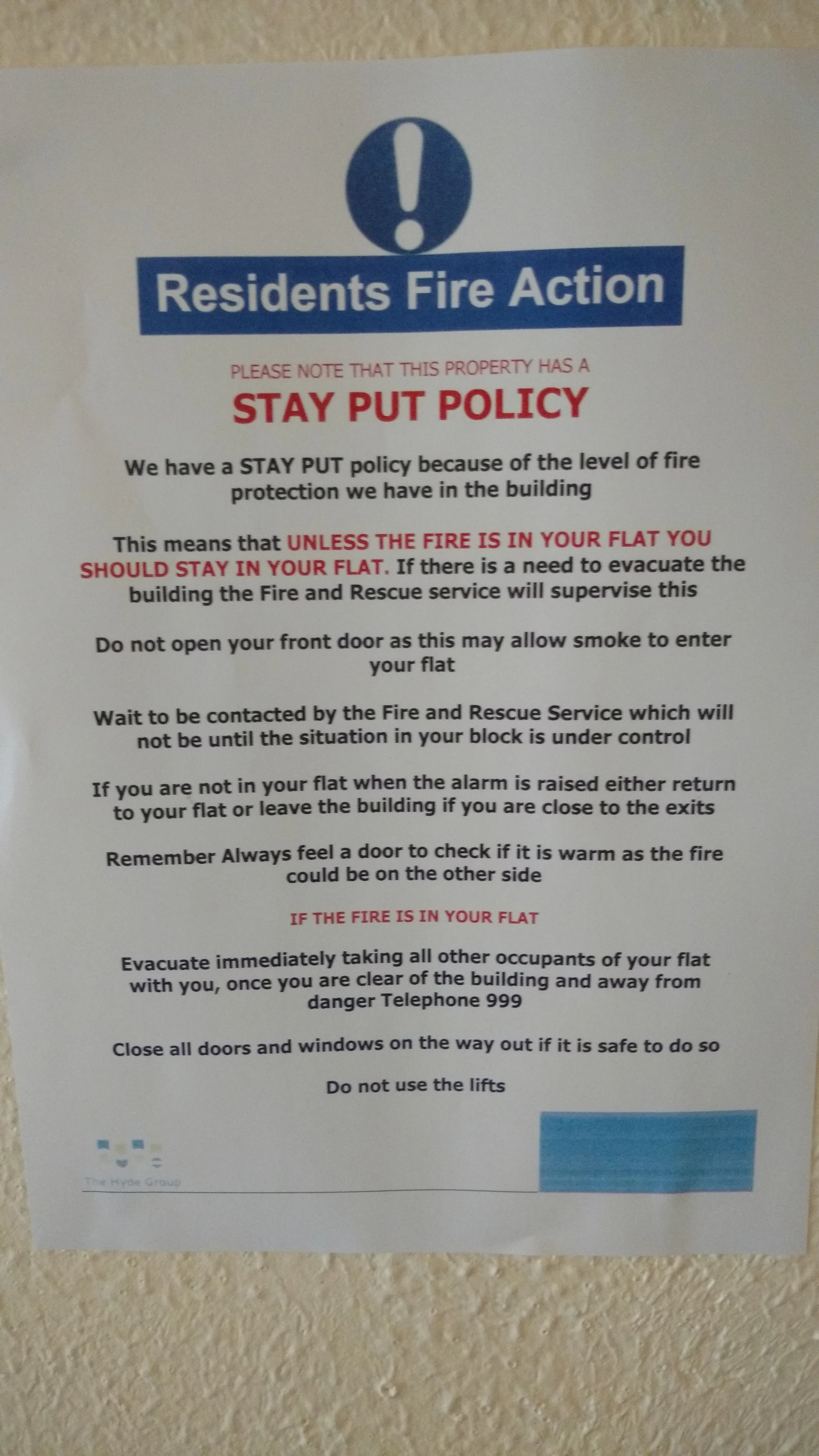

My dad really feared a fire in the slum we grew up in and was constantly on the landlord's case about the wiring in the building. My dad bought this rope from Bon Marche in Brixton that he hoped would save our lives and used to run weekly (tiresome) fire drills, an event recalled in a very early episode of Daniel Ruiz Tizon is Available in late 2012.

We lived on the top floor of a death trap. We would not have survived a fire, even though it was a long rope. My dad would tie the rope of hope around each of our waists and we'd all amble over to the window and after that, there was no plan. I think my dad thought it’d be like an episode of Batman where the recently departed Adam West and Burt Ward (Robin) would scale a wall, holding a normal conversation as they went about their business and everything would go smoothly.

Fast forward three decades and in SW8, ridiculous glass towers are crowbarred into what’s left of a large working class community that has been gradually pushed out since 2008. Big 4 by 4s, often with personalised number plates, have started to appear on the roads. There are tooth whitening clinics and high end CHICKEN shops. Gyms seemingly on every corner. Young professionals exit the gated new builds, yoga mats slung over their shoulders or with rucksacks on their backs as they run to work. Others unfold their Bromptons. Hardly anybody seems to walk to work these days.

Old familiar faces began to disappear from the community. Sometimes you hear they've moved to the end of the Northern Line. Sometimes you just hear nothing as in the case of the still AWOL Urinating Dwarf of SW8 who hasn’t been seen now since 2013. There are more streets that no longer feel like they're for you. Gated developments continue to spring up wherever there's any space left to build. High vis vested builders are everywhere and I often wonder if they’re ever curious about the negative impact of their work on the community. Very little of the new builds and businesses seem to serve or interact with what was there before they arrived.

Old cafes and bars you drank in turn into hotels. Tourists now walk through the streets you played on as a kid. Streets that aren't even in central London. Believe me, it is strange to hear Vauxhall described as Central London. It isn’t. And I have yet to find a new build in Stockwell and South Lambeth that doesn’t claim to be just ten minutes from Oxford Circus. You could live for a thousand years and drive every day from your new build to the West End and you would not get there in less than ten minutes.

The media are up in arms when they discover the type of super wealthy people buying up the glass tower penthouses that have overwhelmed the south side of the Thames. The people on the surrounding estates, the Wyvill, Mawbey Brough, they had an idea. They knew it wasn't people like them that would be moving in. London post ’08 is Ivor Lott and Tony Broke, the old Cor!! and later Buster comic strip. And that divide just keeps getting bigger and bigger. You keep, as a close friend often says, 'biting into the pillow so hard you're ingesting pillow foam'.

You vote at the Election all the while knowing your life has long reached a point where you know whatever the outcome, it changes nothing for you.

You're on Bread and Water, along with hundreds of thousands of Londoners. You keep battling away, working harder than ever. Longer hours. Less sleep.

But nothing changes for you.

Nothing changes.

Nothing changes.

Nothing changes.

And that for me is the story of life in London.

Which of the people who make the decisions that run the country know what it’s like to be able to see the bathroom regardless of where you stand in your tiny studio flat? At least these days I don’t have to leave the flat to get to the bathroom.

I grew up in an absolute slum of a place with no hot water. We all, a family of four, slept in a single room. The bathroom was shared with 13 people. This wasn’t for a year or two until we got a council flat. We lived like this for 24 years. That squalor, the damp, the cold, the lack of hope, broke us as a family. Only two of us lived to tell the tale, my dad disappearing two and a half years after my mum passed away. Both parents were the youngest in their family and were outlived in both cases by siblings twenty years older. My dad was a very strong and fit man.

It was the poverty and the absence of hope that our circumstances would change that did for them.

Poverty kills.

Poverty kills.

Poverty kills.

That place will never leave me.

I wake up so many nights and I am still there in that place. And a part of me will always be there. So HOUSING has always been a THING with me. And I never understood why it was ignored by the media for way too long. Bad housing will change your life forever. Bad housing will always leave you having to work harder than other people. General Elections would come and go and really by the 2005 Election, I thought housing would be a big issue. And it wasn’t.

I had returned to the country in 2003 after a brief time abroad to begin looking for another flat anew and began to see that you now got less for your money. Unless you were going to share, the housing stock, and this is private rented accommodation I’m talking about here (despite 35 years in my home borough, Lambeth were never going to house me) was getting noticeably poorer. Bereavement meant I no longer felt inclined to stay in south London so I looked all over the capital and the poor quality of housing was the same all over the city. I saw many awful places, like the one I saw in Baker Street where there was a standalone shower cubicle in the kitchen, right next to the fridge, that took years to forget about. That one was just under £700pcm.

Per Calendar Month. Landlords and Lettings Agents love that term.

Just under a decade later, in the midst of another intense flat hunting period, and something again covered in an early episode of my Available podcast, I viewed an absolute dive in Tooting Bec, SW17. It was a top floor flat. I’m a top floor kind of guy. I noticed the garden below was in a very worrying state and while I wouldn’t be using the garden, the garden told me everything I needed to know about the place. As we headed out of the building, I vented my disgust about the state of the place at the lettings agent who had even arrived late. As we reached the front door, an Asian guy peeked out through the door of a room on the ground floor and I caught more than a glimpse of another seven guys sleeping on the floor of that room. That’s London. And that was just a few months after London 2012, a two week sporting feast I did not buy into from the beginning, so much so that I came off twitter that summer so as to avoid it. Five years on, we can see there was no 2012 legacy. The country’s appetite for fried chicken is if anything stronger than ever and rent prices in East London rocketed, pricing out much of the pre-Games community. How is that fair? But hey, the masses need to share in an experience. They had their experience. Look where the city is now.

Up until that summer, living in a block of flats in Stockwell, I had fought tooth and nail with a landlord on repairs and out of my own pocket, regularly replaced the batteries in the faulty smoke alarms on all landings that prevented me from sleeping. Inevitably, I still had money deducted from my deposit on my checkout inventory.

From 1976 to 2000, I’d have to leave the family bedsit to get to the bathroom. The night-time anxiety was always considerable because I didn’t want to be having to leave the bedsit, especially in winter.

The morning of my mum’s death may have been the most confusing day of my life. I awoke in my fold up bed of the last 11 years in the room I by then just shared with my mum (my sibling was by then abroad after university and my dad, well, he’d taken another bedsit a floor below, but that’s another story). I got up, folded the bed together, went to Soho, signed my first television deal which gave me hope that I’d finally be able to get us out of the squalor, only to find my mum dead in the flat in the early afternoon. She had said to me not long before that she would die in that house and it will always haunt me that I could never get us to a place with hot water, our own bathroom and heating which would’ve extended her life. However, despite the hardship posed by living under those conditions every day, there was a real sense of community there and I remain in touch with those neighbours still alive. They are some of the greatest people I have ever met. What I learned a while back about those without money is they are the ones who give you everything they have.

Despite that very difficult opening chunk of my life, to this day I do not give a monkey's about owning property. I never got that national obsession. My ambitions lay elsewhere. I just wanted to live somewhere I could be happy and sell my writing. To this day, the former remains a problem and the second is very much up and down, making the former I suppose near impossible.

It was never easy selling work to broadcasters who often didn’t know the world I was writing about. I still remember the Head of Comedy who commissioned one of my pilots asking me “What happens on council estates?” I knew then it would be hard for that show to go the final step towards being made. And now, almost a decade later, it’s even harder to sell work because the commissioning editors and agents are about fifteen years younger than you, and still have no clue about the world you’re writing about. They are of course normally still white. It’s hard to see that changing in the media.

It bothers me that we have only just started talking about the Housing Crisis in the last few years when it's been a problem since the early 00s. When I used to do the nightly housing tweets last year, I'd get tweets from people telling me they had no idea the housing crisis was so bad. And I've got to say, that took me aback. If I’m a poor person that knows there are very wealthy people out there (indeed, my mum was one of many Iberian maids that cleaned the houses of the super rich in Belgravia for a quarter of a century so I was exposed to that world early), how is that there are well off people who have been clueless for so long about how those on the other side of the divide live? Incidentally, those housing tweets stopped because a paper blew them up into a story and dismissed 4 years’ worth of work as a ‘rant’.

Small things stay with me about the old family bedsit. Like always, to this day, washing my hands with cold water because for 24 years, I had no hot water. Like sleeping under a ton of bedding because for 24 years we had no heating. I can remember the way the grain changed on the curve of the bannister as we reached the top floor landing. The way the floor creaked as you entered the front room. I remember the all-too brief arrival of the Ascot Water heater in September ’89 which pleased my landlord who, much the way JFK had predicted the US would have a man on the moon before the sixties were out, had promised us hot water before the nineties arrived. Within three days, the water heater had blown up and British Gas had placed a Do Not Use Sticker on it, a sticker which the landlord duly removed.